Long COVID, IVF success and the Delta variant: some of our most-read medicine stories of 2021

For the second year running, it was no surprise readers were still hungry for COVID-19 stories as new findings and variants emerged in 2021.

For the second year running, it was no surprise readers were still hungry for COVID-19 stories as new findings and variants emerged in 2021.

As we ticked over to 2021, there was no telling what the year was going to bring with the COVID-19 pandemic throwing curve balls such as the emergence of newer and fitter variants like Delta and researchers trying to understand the long-term effects of contracting COVID-19. Then of course there were the uplifting stories far removed from the pandemic news cycle, such as the UNSW-developed website that enabled patients to calculate their chance of IVF success.

Let’s revisit five of our most-read medicine and health stories of the year as we say goodbye to another challenging year, but a year that also gave us hope, with medical success stories such as the COVID-19 vaccine.

The SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant was initially detected in India back in December 2020. It swept rapidly through India before reaching the UK, the USA, followed by the rest of the world. At the time, there were concerns among scientists this more contagious strain would become the dominant strain. After almost a year, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recently announced the Delta variant represented 99% of sequenced COVID-19 cases globally.

Researchers initially indicated the Delta variant was the most transmissible variant yet — as much as 60 per cent more contagious than the Alpha variant. When we spoke to Dr Francesca Di Giallonardo, a virologist at The Kirby Institute at UNSW Sydney in July 2020, we asked if the Delta variant had the capacity to outcompete other variants of concern.

“Most probably yes, as this is a common process in natural selection and immune escape. However, the timeline and characteristics of variant replacement may vary between different geographic regions, particularly in those isolated by border closures.

“Prediction of infectivity of new variants is not trivial. In general, viruses increase their transmissibility. That means that the most ‘successful in transmission’ variant outcompetes other variants. However, it’s almost impossible to predict which variant will win the race and when we have reached the point of most transmissible,” said Dr Di Giallonardo.

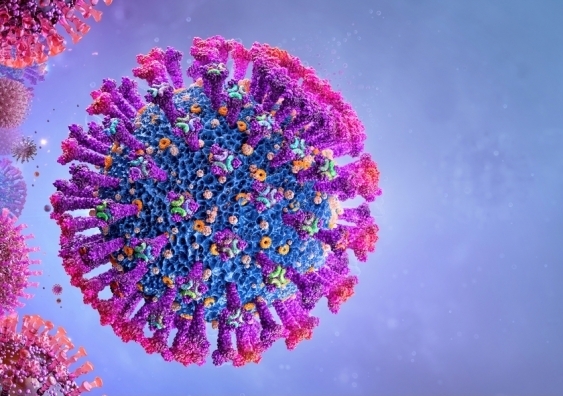

Researchers initially indicated the Delta variant was the most transmissible variant yet — as much as 60 per cent more contagious than the Alpha variant. Image: Shutterstock

While newsfeeds were awash with COVID-19 stories at the beginning of 2021, this uplifting IVF story provided future parents with hope. In February 2021, the YourIVFSuccess website was launched, making comparisons between Australian clinics easier and more transparent for future parents.

Funded by the federal government, the new online tool was developed by the National Perinatal Epidemiology Statistics Unit (NPESU) at UNSW.

With the new platform, patients have access to a new online estimator that allows couples to predict their chances of successfully having a baby based on their individual characteristics.

“IVF has helped hundreds of thousands of Australians become parents. But until now, there hasn’t been an easy way to find and compare fertility clinics or to estimate an individual's chance of treatment success,” said Professor Georgina Chambers, Director of the NPESU.

“The YourIVFSuccess prediction model, called the IVF Patient Estimator, is the most contemporary and comprehensive estimation calculator for IVF success in the world. It will help those thinking about starting, or continuing IVF, make more informed choices and to predict their chances of having a baby.”

Professor Georgina Chambers. Image: UNSW

The term ‘long COVID’ was coined in May 2020 by Dr Elisa Perego on Twitter who lived in Lombardy, Italy – one of the hardest hit COVID-19 hotspots early in the pandemic. The term summarised her experience of the disease as cyclical, progressive, and multiphasic. Several months later, the phrase was being used in mainstream media and eventually led to organisations such as the WHO to adopt the phrase in its communications.

As COVID-19 cases increased around the world, so did the number of patients suffering from a longer, more complex course of illness after contracting the virus compared to initial cases in Wuhan. It seemed the latest challenge for medical researchers was this post COVID-19 syndrome called long COVID. But what exactly is long COVID and what do we know about it?

Since April 2020, UNSW Sydney medical researchers have been investigating the long-term effects of COVID-19 to develop improved post-COVID-19 clinical care and help guide future health service requirements. This is part of the ADAPT study at the Kirby Institute where researchers have been following patients diagnosed with COVID-19 at regular intervals over a minimum of one year post-diagnosis.

Professor Gail Matthews from the Kirby Institute, who is one of the lead investigators of the study, said there was no clear definition for long COVID yet, and it was likely to be several different syndromes with different causes.

“Generally, long COVID refers to people who don't recover from the acute COVID-19 infection and go on to have longer-term symptoms. The acute phase of illness can last up to two weeks, but beyond that, you potentially have a post-acute illness, or what is now called long COVID. Most people are tending to use a period for long COVID at around the two to three months mark,” Professor Matthews said.

“It's very hard to come down to a clear definition, and there is no accepted global definition. But most accept the common symptoms being fatigue, shortness of breath, tightness in the chest, racing heart, difficulty concentrating and brain fog.

“There are probably several different syndromes that cause long COVID. In other words, long COVID isn't just one thing. There can be many underlying causes for somebody still being persistently symptomatic three months-plus after infection,” she explained.

“The question is, why aren’t these people better? Why wouldn't they have recovered as they should have if they had the flu or another viral illness?": Professor Gail Matthews. Photo: Supplied

In July 2021, a study led by UNSW and NeuRA showed that people with chronic pain had an imbalance of neurotransmitters in the part of the brain responsible for regulating emotions.

The study suggested this imbalance could be making it harder for people to keep negative emotions in check – and the researchers said persistent pain might be triggering the chemical disruption.

More than three million Australians experience chronic pain: an ongoing and often debilitating condition that can last from months to years. This persistent pain can impact many parts of a person’s life, with almost half of people with chronic pain also experiencing major anxiety and depression disorders.

“Chronic pain is more than an awful sensation,” said senior author of the study Associate Professor Sylvia Gustin, a neuroscientist and psychologist at UNSW and NeuRA. “It can affect our feelings, beliefs and the way we are.

“We have discovered, for the first time, that ongoing pain is associated with a decrease in GABA, an inhibitive neurotransmitter in the medial prefrontal cortex. In other words, there's an actual pathological change going on.”

Regulating emotions might be harder for people with chronic pain, the study finds. Photo: Shutterstock

In May 2021, researchers at UNSW Sydney’s Kirby Institute revealed they had developed cells that allowed them to test the effect of SARS-CoV-2 faster than anywhere else in the world.

The team, led by Associate Professor Stuart Turville, used these genetically “supercharged” cells to quickly understand the dynamics of different variants of the virus, testing their ability to evade vaccines, and to inform the public health response in real time.

The scientists shared microscopic footage of the process and in their incredible video, you could see the healthy supercharged cells being taken over by the SARS-CoV-2 virus over a 20-hour period.

“The SARS-COV-2 virus melts into healthy cells. That’s what enveloped viruses do, melt the outer layer of themselves with the outer layer of a cell in a process called “fusion”. So instead of the virus particle melting into a cell, the infected cells melt with their neighbour and so on like a set of dominos,” says Associate Professor Turville. “At the end we see the virus has turned the cells into large balls.”

The team looked at hundreds of different cells to identify ones that would allow the virus to replicate as quickly and effectively as possible. Photo: Richard Freeman / UNSW